The First Endorsement

From Jackson, Mississippi to the Senate Floor.

Hyperlinks lead to primary sources.

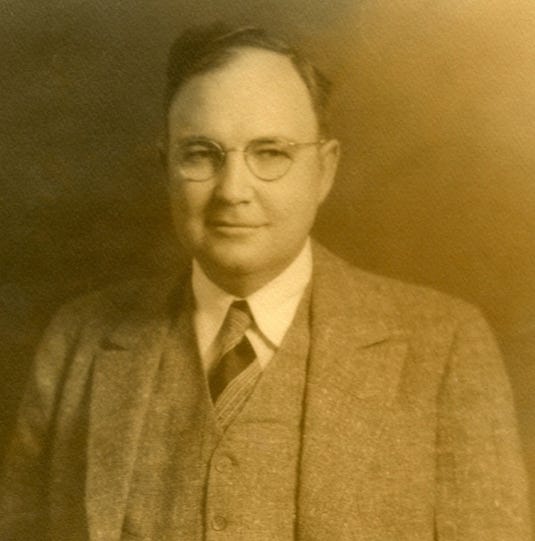

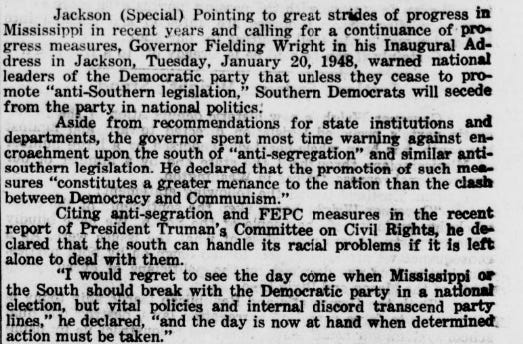

Fielding Wright’s 1948 inaugural address left little room for interpretation. He made clear that the issue was not negotiation, delay, or moderation, but separation.

During his fiery speech, he warned the Democratic Party that unless it stopped promoting “anti-Southern” legislation, Southern Democrats would secede from the National Party. He spent most of his speech focused on the intrusion upon the South with anti-segregation, Truman’s Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC), anti-lynching bills, anti-poll tax bills, and other legislation aimed at defeating racial discrimination. Wright even accused the National Democratic Party of seeking to wreck the South and all its institutions.

He declared, “The South will no longer tolerate being the target for legislation, which would not only destroy our lives but which, if enacted, would destroy the United States of America.”

Wright spoke about how the Southern Democrats had always adhered to the National Democratic Party. Then he added, “When the national leaders attempt to change those principles for which the party stands, we intend to fight for its preservation with all means at our hands. I would regret to see the day come when Mississippi or the South should break with the Democratic Party in a national election.”

He claimed that Southerners were already solving racial problems in a wholesome and constructive manner. “Here in Mississippi and in the South,” he said, “maybe found the greatest examples in human history of harmonious relationships ever recorded as existing between two so different and distinct races as the white and the negro, living so closely together and in such nearly equal numbers.”

Wright cast his defiance as loyalty. Southern Democrats, he insisted, had always adhered to the national party’s principles. If those principles had changed, then resistance was not rebellion, but preservation. Secession, in this telling, was not abandonment. It was self-defense.

The answer came two days later.

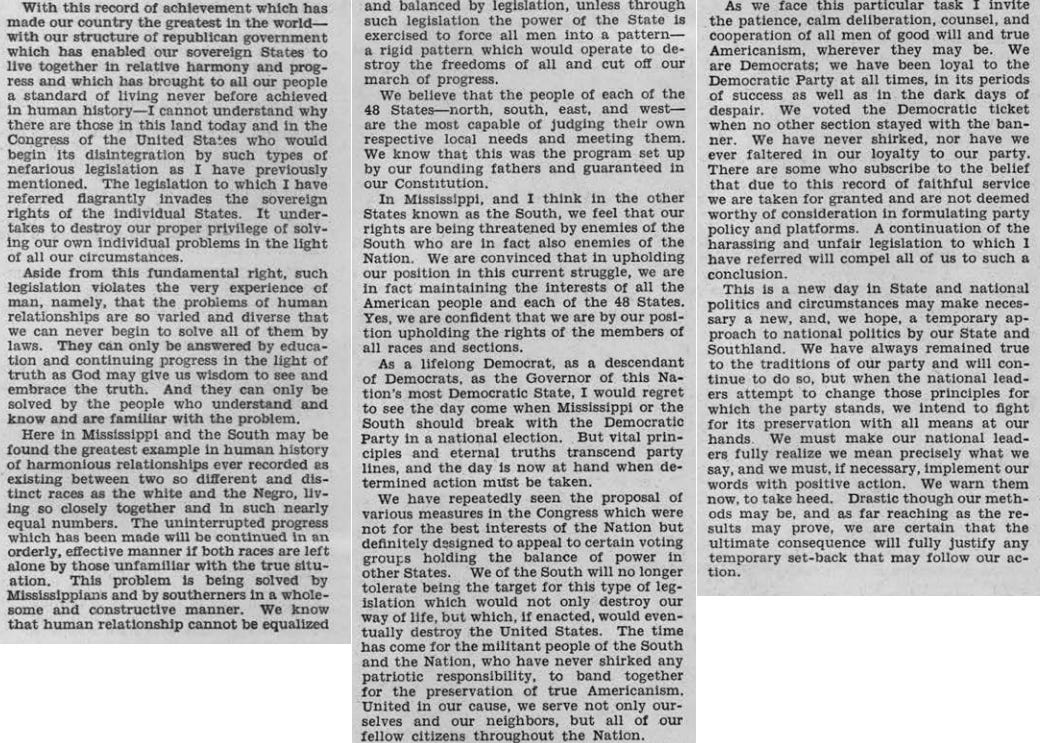

James Eastland: One of Mississippi’s most powerful political figures of the 20th Century.

At the time, James Eastland was a sitting United States Senator and a conservative Democrat with deep roots in Mississippi’s political establishment. Eastland represented the federal arm of Southern resistance and understood how to translate state defiance into national leverage.

For readers familiar with the history of Fannie Lou Hamer, Eastland is the Mississippi planter she so often referenced. Their intertwined history is examined in the 2008 book The Senator and the Sharecropper: The Freedom Struggles of James O. Eastland and Fannie Lou Hamer by Chris Myers Asch.

When Eastland spoke, he was assessing Wright’s rhetoric. And when he chose to endorse Wright’s stand publicly, he did so with the authority of Washington behind him.

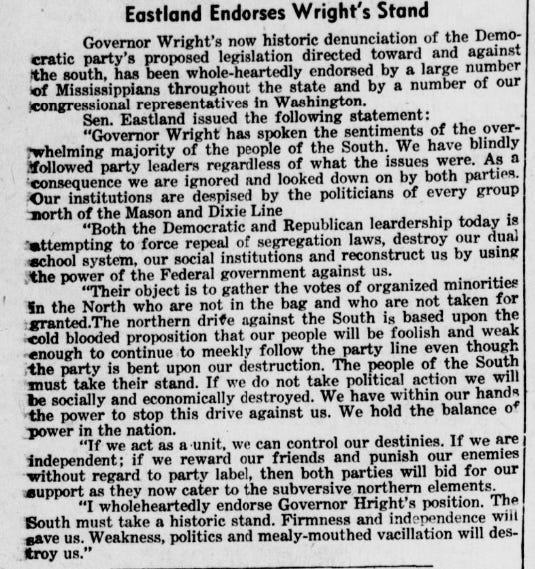

Two days after Wright’s inaugural address, Eastland issued a statement in the Durant News that made clear the governor had not spoken alone.

James Eastland said, “Governor Wright has spoken to the sentiment of the overwhelming majority of the people of the South. We have blindly followed party leaders, regardless of what the issues were. As a consequence, we are ignored and looked down upon by both parties. Our institutions are despised by the politicians of every group North of the Mason and Dixie lines.

“Both the Democratic and Republican leadership today is attempting to force the repeal of segregation laws, destroy our dual school system, our social institutions, and reconstruct us by using the power of the Federal government against us.

“Their objective is to gather the votes of organized minorities in the North who are not in the bag and who are not to be taken for granted. The Northern drive against the South is based upon the cold-blooded propositions that our people will be foolish and weak enough to continue to meekly follow the party line, even though the party is bent upon our destruction. The people of the South must take their stand. If we do not take political action, we will be socially and economically destroyed. We have within our hands the power to stop this drive against us. We hold the balance of power in the nation.”

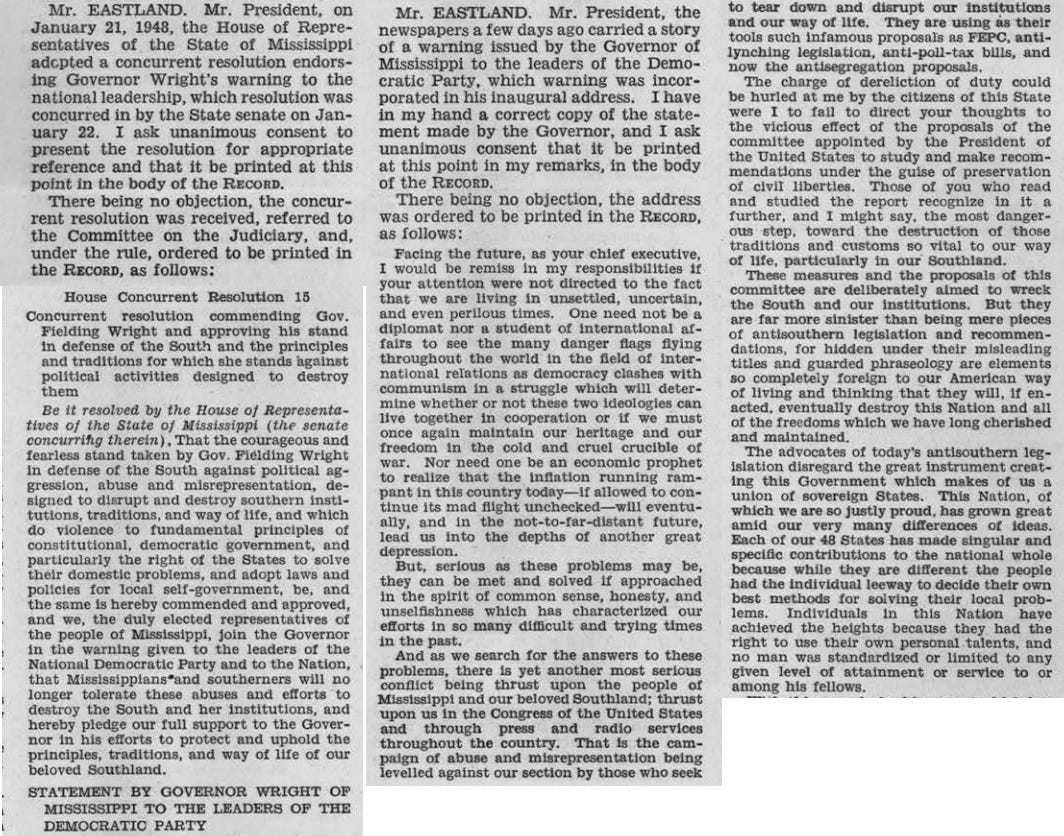

On January 23, Senator Eastland entered a resolution on behalf of Mississippi into the US Congressional Record.

What the Congressional Record preserves is both rhetoric and ratification.

The resolution commended Wright for what it described as a “courageous and fearless stand” in defense of Southern traditions and institutions. It framed civil rights legislation as political aggression, abuse, and misrepresentation aimed at disrupting Southern society and undermining the constitutional principle of “states’ rights.” Federal civil rights proposals were cast as deliberate attempts to destroy local self-government under the guise of preserving liberty.

Throughout the text, civil rights enforcement is repeatedly equated with foreign ideology, centralized control, and social reconstruction imposed by force. Segregation is defended through appeals to “tradition,” “way of life,” and the supposed harmony of existing race relations. The resolution insists that Mississippi and the South are already addressing human relations constructively and warns that outside intervention will only lead to conflict and national ruin.

Most importantly, their solution does not frame its support as partisan rebellion. Like Wright, it casts resistance as loyalty. Mississippi is portrayed as faithful to the Democratic Party’s historic principles, even as it warns that continued federal pressure will make separation unavoidable. The resolution closes with a pledge of full support for the governor’s position and a call for unified Southern action to protect what it defines as true Americanism.

In other words, Wright’s threat did not remain a governor’s speech. Within days, it had been endorsed by both chambers of Mississippi’s legislature and entered into the official record of Congress. What began as a warning had become a rallying cry.

And James Eastland wasn’t the only politician to have a quick response to Wright’s threats.

This work follows the Southern Strategy and other moments in American political history that tend to get flattened or forgotten. It focuses on the long arc of political realignment, the choices made along the way, and what gets lost when we rely on simplified narratives. If this work matters to you, subscriptions (free or paid) help support it.